By Spencer D Gear PhD

This was an audacious request on a Christian forum that did not seem to indicate too much thought about the question: ‘Where in scripture does it tell us which books of the bible are to be included in the bible? (table of contents)’[1]

How should I respond?

1. No need to inform first century Christians

There was no need to tell the Christians of the first century.[2] They knew which books were included in the OT canon. That’s why Paul could say to the Berean Christians in Acts 17:11 (ESV): ‘Now these Jews were more noble than those in Thessalonica; they received the word with all eagerness, examining the Scriptures daily to see if these things were so’. Which Scriptures?

Isn’t that amazing that the Book of Acts does not need to articulate a list of the Books of the OT so that the Berean Christians would know which books were in the OT and which were out of it? Paul did not have to list them and say, ‘Here is a list of the books contained in Scripture that you should use to check the authenticity and validity of my teaching’. They knew which books were in the OT canon.

And they did not include the Apocrypha in the Hebrew OT (Wayne Grudem).

In the four NT Gospels, I do not read that there was any dispute between Jesus and the Jewish leaders over the extent of the OT canon.

2. Persistence: No list of books in the canon

The forum fellow persisted in another thread: ‘Scripture does not give us a list of books that are to be in the Bible. How do we know we have the right books in the Bible? Scripture is silent about it’.[3]

My response was:[4]

Because the OT and NT do not give a list of books that are inspired of God to be included in the Bible does not mean that what we have is illegitimate. In fact, the word, Bible, appears nowhere in the Bible (that I’m aware of), so why are you supporting the use of the term, Bible?

However, God gave teachers to the church (1 Cor 12:28 ESV; Eph 4:11 ESV) who guide us through that process. These teachers themselves are not perfect in their understanding as Paul told the Bereans (Acts 17:11 ESV) that they were to check his teaching against the Scripture. Which Scripture? The OT. Paul didn’t say in Acts 17, here’s a list of the OT books that you need to use to check my teaching. They knew what they were as affirmed by the Jews.

3. Pseudo-gospels readily available

In the first century and beyond, there were plenty of fake gospels available. Do you want the pseudo-gospel of Peter (GPet) to be in the NT? It was rejected by the early church fathers because of its heretical teachings. It was found with the Qumran documents. It was mentioned by early church historian, Eusebius in his Church History (3.3.1-4; 3.25.6; and 6.12.3-6).

Why not also the Gospel of Thomas (written about mid to late second century)?[5] If you read the Gospel of Thomas and compare it with each of the 4 Gospels in the NT, you will notice the marked difference in content. I’d suggest a read of Nicholas Perrin’s, Thomas, the Other Gospel (Perrin 2007). Perrin concludes his book with this comment:

Is this the Other Gospel we have been waiting for? Somehow, I suspect, we have heard this message before. Somehow we have met this Jesus before. The Gospel of Thomas invites us to imagine a Jesus who says, ‘I am not your saviour, but the one who can put you in touch with your true self. Free yourself from your gender, your body, and any concerns you might have for the outside world. Work for it and self-realization, salvation, will be yours – in this life.’ Imagine such a Jesus? One need hardly work very hard. This is precisely the Jesus we know too well, the existential Jesus that so many western evangelical and liberal churches already preach.

If the Gospel of Thomas is good news for anybody, it is good news to those who are either intent on escaping the world or are already quite content with the way things are (Perrin 2007:139).

This Gospel of Thomas is a different Gospel, “a Christianized self-help philosophy” (Perrin 2007:139). See my article of assessment: Is the Gospel of Thomas genuine or heretical?

4. The walking, talking cross of Gospel of Peter

(walking, talking cross: image courtesy NT Blog, Mark Goodacre)

(walking, talking cross: image courtesy NT Blog, Mark Goodacre)

As for the Gospel of Peter [GPet], please read this assessment by C L Quarles (2006). Here are a few grabs from Quarles’ critique of GPet:

Such compositional projection and retrojection [of GPet] are absent from the canonical Gospels. This suggests that the authors of the canonical Gospels were constrained to preserve faithfully the traditions about Christ, but that the author of GP felt free to exercise his imagination in creative historiography. The compositional strategy of projection suggests that the GP shares a common milieu with second-century pseudepigraphical works and casts doubt on [John Dominic] Crossan’s claim that the GP antedates the canonical Gospels….

Compositional strategies that were popular in the second century can readily explain how the author of the GP produced his narrative from the canonical Gospels….

The GP is more a product of the author’s creative literary imagination than a reflection of eyewitness accounts of actual events (Quarles 2006:116, 119).

Charles Quarles has an online assessment of GPet HERE.

Of the Gospel of Judas, the National Geographic reported:

Stephen Emmel, professor of Coptic studies at Germany’s University of Munster, analyzed the Gospel of Judas and submitted the following assessment.

“The kind of writing reminds me very much of the Nag Hammadi codices,” he wrote, referring to a famed collection of ancient manuscripts.

“It’s not identical script with any of them. But it’s a similar type of script, and since we date the Nag ‘Hammadi codices to roughly the second half of the fourth century or the first part of the fifth century, my immediate inclination would be to say that the Gospel of Judas was written by a scribe in that same period, let’s say around the year 400.”

Here is another assessment of the ‘other gospels’ in an article on ‘the historical reliability of the Gospels’ by James Arlandson. He wrote:

The Gnostic authors often borrowed the names of Jesus’ disciples to attach to their texts, such as the Gospel of Peter, the Gospel of Thomas, the Gospel of Philip, and the Gospel of Mary. The Gospel of Judas has been discovered, restored, and published most recently. Using the disciples’ names or other Biblical names gives the appearance of authority, but it is deceptive. The original disciples or Bible characters had nothing to do with these writings. The teaching of Jesus, the names of his disciples, and the four Gospels traveled well. Gnostics capitalized on this fame.

All of these (late) Gnostic documents would not be a concern to anyone but a few specialists. Yet some scholars, who have access to the national media and who write their books for the general public, imply that Gnostic texts should be accepted as equally valid and authoritative as the four canonical Gospels, or stand a step or two behind the Biblical Gospels. At least the Gnostic scriptures, so these scholars say today, could have potentially been elevated to the canon, but were instead suppressed by orthodox church leaders. (Orthodox literally means “correct or straight thinking,” and here it means the early church of Irenaeus and Athanasius, to cite only these examples).

This series challenges the claim that the Gnostic texts should be canonical or even a step or two behind the four Biblical Gospels. The Gnostic texts were considered heretical for good reason.

5. Reasons to reject ‘other gospels’

There are scholarly and practical reasons why the Gospel of Thomas, the Gospel of Peter (GPet), the Gospel of the Ebionites, Gospel of Marcion, the Gospel of Judas, the Gospel of Mary and other pseudo-gospels were not chosen over the four NT Gospels.

I examined why some of the content of these pseudo-gospels are not included in the NT in my doctoral dissertation. Take a read of the Gospel of Peter (online) and it should become evident why such fanciful imagination is not included in the NT. This section of GPet states:

35 Now in the night whereon the Lord’s day dawned, as the soldiers were keeping guard two by two in every watch, 36 there came a great sound in the heaven, and they saw the heavens opened and two men descend thence, shining with (lit. having) a great light, and drawing near unto the sepulchre. 37 And that stone which had been set on the door rolled away of itself and went back to the side, and the sepulchre was

X. 38 opened and both of the young men entered in. When therefore those soldiers saw that, they waked up the centurion and the elders (for they also were there keeping 39 watch); and while they were yet telling them the things which they had seen, they saw again three men come out of the sepulchre, and two of them sustaining the other (lit. the 40 one), and a cross following, after them. And of the two they saw that their heads reached unto heaven, but of him that 41 was led by them that it overpassed the heavens. And they 42 heard a voice out of the heavens saying: Hast thou (or Thou hast) preached unto them that sleep? And an answer was heard from the cross, saying: Yea.

Here we have a walking and talking cross that came out of the sepulchre – fanciful nonsense! One does not have to be very astute to reject this kind of extra ‘gospel’, yet John Dominic Crossan of the Jesus Seminar believes GPet is the original Cross Gospel from which the other Gospels derived this information (Crossan 1994:154-155).

6. Questions about formation of the NT canon

I still have some questions about the formation of the NT canon that remain unanswered at this time. Historically, there was a partial list available, known as the Muratorian Canon (ca. AD 170-200).[6] My questions surround the process of formation of the canon that included the procedure used to determine if a book was theopneustos (breathed out by God – 2 Tim 3:16-17 ESV). I had questions about two church councils in the late third century that finally affirmed the NT canon.

Historical details include the following:

The first historical reference listing the exact 27 writings in the orthodox New Testament is in the Easter Letter of Athanasius in 367 AD. His reference states that these are the only recognized writings to be read in a church service. The first time a church council ruled on the list of “inspired” writings allowed to be read in church was at the Synod of Hippo in 393 AD. No document survived from this council – we only know of this decision because it was referenced at the third Synod of Carthage in 397 AD. Even this historical reference from Carthage, Canon 24, does not “list” every single document. For example, it reads, “the gospels, four books…” The only reason for this list is to confirm which writings are “sacred” and should be read in a church service. There is no comment as to why and how this list was agreed upon (Baker 2008).

Church historian, Earle Cairns, answers some of these issues with this assessment of the development of the list of books that became known as the NT:

People often err by thinking that the canon was set by church councils. Such was not the case, for the various church councils that pronounced upon the subject of the canon of the New Testament were merely stating publicly … what had been widely accepted by the consciousness of the church for some time. The development of the canon was a slow process substantially completed by A.D. 175 except for a few books whose authorship was disputed (Cairns 1981:118).

Cairns explained further why there was a delay in accepting certain NT books as canonical:

Apparently the Epistles of Paul were first collected by leaders in the church of Ephesus. This collection was followed by the collection of the Gospels sometime after the beginning of the second century. The so-called Muratorian Canon, discovered by Lodovico A. Muratori (1672-1750) in the Ambrosian Library at Milan, was dated about 180. Twenty-two books of the New Testament were looked upon as canonical. Eusebius about 324 thought that at least twenty books of the New Testament were acceptable on the same level as the books of the Old Testament. James, 2 Peter, 2 and 3 John, Jude, Hebrews, and Revelation were among the books whose place in the canon was still under consideration.[7] The delay in placing these was caused primarily by an uncertainty concerning questions of authorship. Athanasius, however, in his Easter letter of 367 to the churches under his jurisdiction as the bishop of Alexandria, listed as canonical the same twenty-seven books that we now have in the New Testament. Later councils, such as that at Carthage in 397, merely approved and gave uniform expression to what was already an accomplished fact generally accepted by the church over a long period of time. The slowness with which the church accepted Hebrews and Revelation as canonical is indicative of the care and devotion with which it dealt with this question (Cairns 1981:118-119).

Eusebius (ca. AD 265-330)[8] wrote this of the disputed and rejected NT writings:

3. Among the disputed writings, which are nevertheless recognized by many, are extant the so-called epistle of James and that of Jude, also the second epistle of Peter, and those that are called the whether they belong to the evangelist or to another person of the same name.

4. Among the rejected writings must be reckoned also the Acts of Paul, and the so-called Shepherd, and the Apocalypse of Peter, and in addition to these the extant epistle of Barnabas, and the so-called Teachings of the Apostles; and besides, as I said, the Apocalypse of John, if it seem proper, which some, as I said, reject, but which others class with the accepted books (Eusebius 1890, 3.25.3-4).

7. An eminent church historian’s assessment

Philip Schaff’s History of the Christian Church is considered one of the most comprehensive expositions of church history by a near-contemporary scholar. He wrote:

The Jewish canon, or the Hebrew Bible, was universally received, while the Apocrypha added to the Greek version of the Septuagint were only in a general way accounted as books suitable for church reading, and thus as a middle class between canonical and strictly apocryphal (pseudonymous) writings. And justly; for those books, while they have great historical value, and fill the gap between the Old Testament and the New, all originated after the cessation of prophecy, and they cannot therefore be regarded as inspired, nor are they ever cited by Christ or the apostles.[9] (Schaff n.d., vol 3, § 118. Sources of Theology. Scripture and Tradition).

8. Which books were confirmed in the Hebrew OT?

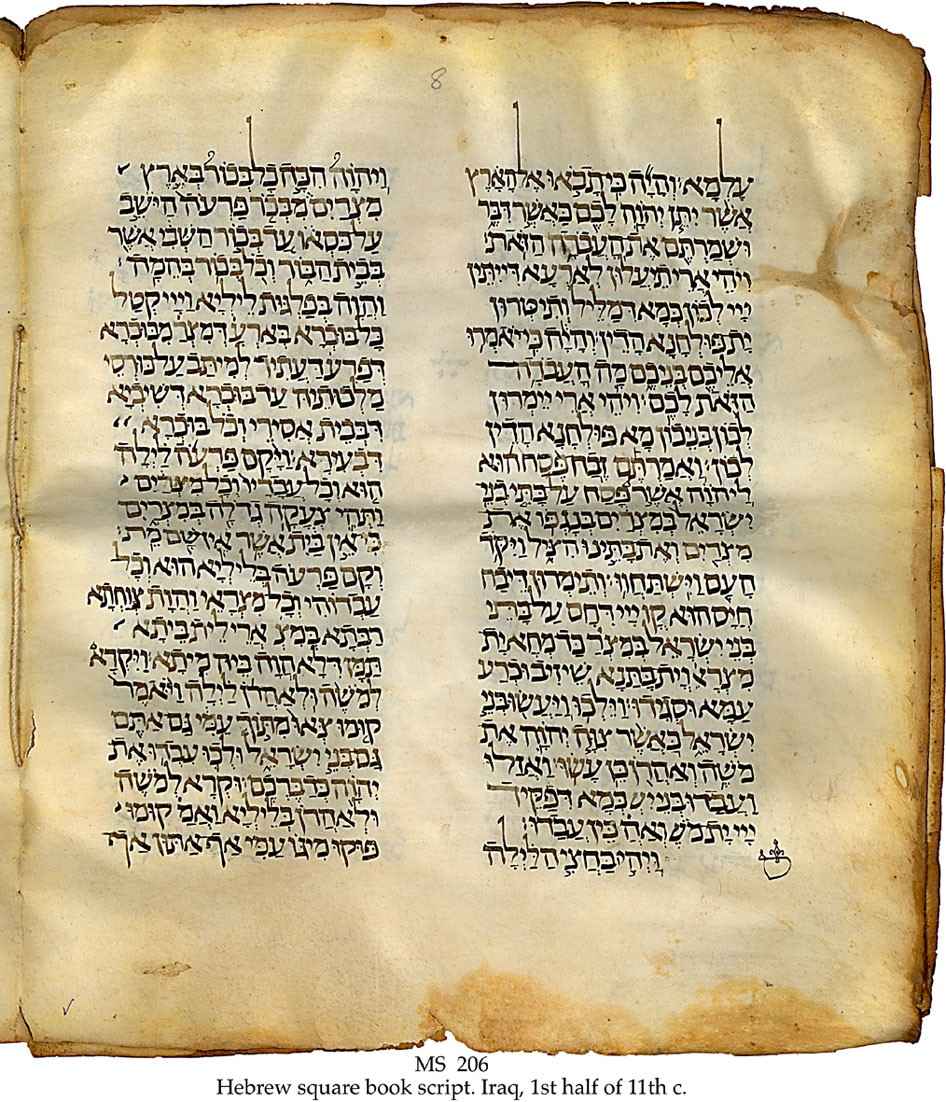

Page from an 11th-century Aramaic Targum manuscript of the Hebrew Bible (Wikipedia)

Which books were included by the Jews in the Hebrew Bible?

I reject the inclusion of the Apocrypha (Deutero-Canonical books) in the OT. This is the position adopted by Roman Catholic authority, Jerome (ca. 347-420),[10] who, in his preface to the Vulgate version of the Apocrypha’s Book of Solomon stated that the church reads the apocryphal books ‘for example and instruction of manners’ but not to ‘apply them to establish any doctrine’. In fact, Jerome rejected Augustine’s unjustified acceptance of the Apocrypha.[11]

The Jewish scholars who met at Jamnia, ca. AD 90, did not accept the Apocrypha in the inspired Jewish canon of Scripture. The Apocrypha was not contained in the Hebrew Bible and Jerome knew it. In his preface to the Book of Daniel in the Hebrew Bible, he rejected the apocryphal additions to Daniel, i.e. Bel and the Dragon, and Susanna.[12] Jerome wrote:

The stories of Susanna and of Bel and the Dragon are not contained in the Hebrew…. For this same reason when I was translating Daniel many years ago, I noted these visions with a critical symbol, showing that they were not included in the Hebrew…. After all, both Origen, Eusebius and Appolinarius, and other outstanding churchmen and teachers of Greece acknowledge that … these visions are not found amongst the Hebrews, and therefore they are not obliged to answer to Porphyry for these portions which exhibit no authority as Holy Scripture ” (in Geisler 2002:527, emphasis added).

The Protestant canon of 39 OT books, excluding the Apocrypha, coincides with the Hebrew 22 books of the OT.

There are many other reasons for rejecting the Apocrypha. Any reasonable person, who reads Tobit, and Bel and the Dragon, knows how fanciful they become when compared with the God-breathed Scripture.

Here are “Some reasons why the Deutero-Canonical material does not belong in the Bible“. Here are examples of theological and historical “Errors in the Deutero-Canonical” books. It was Jerome who introduced the change from calling these books the Apocrypha to Deutero-Canonical.

See my article, Should the Apocrypha be in the Bible?, that gives reasons why the Apocrypha should not be included in the Bible as Scripture.

9. Conclusion

There was no need for the apostles to provide the people of the first century with a list of the OT Books contained in Scripture. It was a given as Paul, the redeemed Pharisee, made evident with his comment to the Berean Christians in Acts 17:11 (ESV). In addition, the Jewish OT canon did not include the Deuterocanonical Books (the Apocrypha).

The Hebrew scholars who met at Jamnia about AD 90 confirmed the 22 OT books in the Hebrew canon of Scripture (which are 39 books in the Protestant canon).

There are good reasons why Gnostic and other gospels were not included by the teachers of the early Christian church in establishing the NT canon. A reading of the Gospel of Thomas, Gospel of Peter, Gospel of Judas, and other pseudo-gospels makes evident that fanciful, speculative, creative content was evidence that these ‘other gospels’ were not the genuine product to include in the NT.

At least 22-23 of the 27 NT books had been affirmed as authoritative for the canon by the late second century. The remainder were questioned because of uncertainty of authorship. However, by the end of the third century, all of the NT canonical books had been gathered and affirmed by church use.

10. Works consulted

Baker, R A 2008. How the New Testament canon was formed. Early Church History – CH101. Available at: http://www.churchhistory101.com/docs/New-Testament-Canon.pdf (Accessed 25 October 2016).

Crossan, J D 1994. Jesus: A revolutionary biography. New York, NY: HarperSanFrancisco.

Eusebius 1890. Church history. Tr by A C McGiffert. Ed by P Schaff & H Wace, from Nicene and Post-Nicene fathers, 2nd series, vol 1. Buffalo, NY: Christian Literature Publishing Co. Rev & ed for New Advent by K Knight at: http://www.newadvent.org/fathers/2501.htm (Accessed 28 October 2016).

Geisler, N 2002, Systematic theology: Introduction, Bible, vol. 1. Minneapolis, Minnesota: Bethany House.

Kirby, P 2016. The Muratorian canon. Early Christian Writings (online), 28 October. Available at: http://www.earlychristianwritings.com/muratorian.html.

Perrin, N 2007. Thomas, the other gospel. London: SPCK.

Quarles, C. L. 2006, The Gospel of Peter: Does it contain a precanonical resurrection narrative? in R B Stewart (ed), The resurrection of Jesus: John Dominic Crossan and N. T. Wright in dialogue, 106-120. Minneapolis: Fortress Press,

Schaff, P n.d. History of the Christian Church: Nicene and Post-Nicene Christianity, A.D. 311-600, vol 3. Available at: Christian Classics Ethereal Library (CCEL), http://www.ccel.org/ccel/schaff/hcc3 (Accessed 25 October 2016).

11. Notes

[1] Christianity Board 2016. When did the universal Church first mentioned in 110AD stop being universal? (online), tom55#231. Available at: http://www.christianityboard.com/topic/23002-when-did-the-universal-church-first-mentioned-in-110ad-stop-being-universal/page-8#entry286284 (Accessed 10 October 2016).

[2] Ibid. This was my response as OzSpen#232.

[3] Christianity Board 2016. What Do You Think Would Have Happened If… (online), tom55#16. Available at: http://www.christianityboard.com/topic/23066-what-do-you-think-would-have-happened-if/#entry286329 (Accessed 10 October 2016).

[4] Ibid., OzSpen#20.

[5] Perrin (2007:viii).

[6] Kirby (2016).

[8] Lifespan dates are from Cairns (1981:143).

[9] Heb. xi. 35 ff. probably alludes, indeed, to 2 Macc. vi. ff.; but between a historical allusion and a corroborative citation with the solemn he graphe legei there is a wide difference.

[10] Lifespan dates are from Cairns (1981:144).

[11] This information is from Geisler (2002:526).

[12] From Geisler (2002:527).

Copyright © 2016 Spencer D. Gear. This document last updated at Date: 28 October 2016.

1. There’s a time factor here that we need to consider. These words are dealing with issues prior to Jesus’ death. While Jesus was on earth he kept the Law (of Moses). Remember what happened according to Matt. 8:4? He told the people to offer the sacrifice that Moses commanded. Jesus Himself went to Jewish festivals privately as we are told in John 7:10. What about the Passover lamb? According to Matt. 26:19, Jesus and the disciples kept the Passover.

1. There’s a time factor here that we need to consider. These words are dealing with issues prior to Jesus’ death. While Jesus was on earth he kept the Law (of Moses). Remember what happened according to Matt. 8:4? He told the people to offer the sacrifice that Moses commanded. Jesus Himself went to Jewish festivals privately as we are told in John 7:10. What about the Passover lamb? According to Matt. 26:19, Jesus and the disciples kept the Passover.