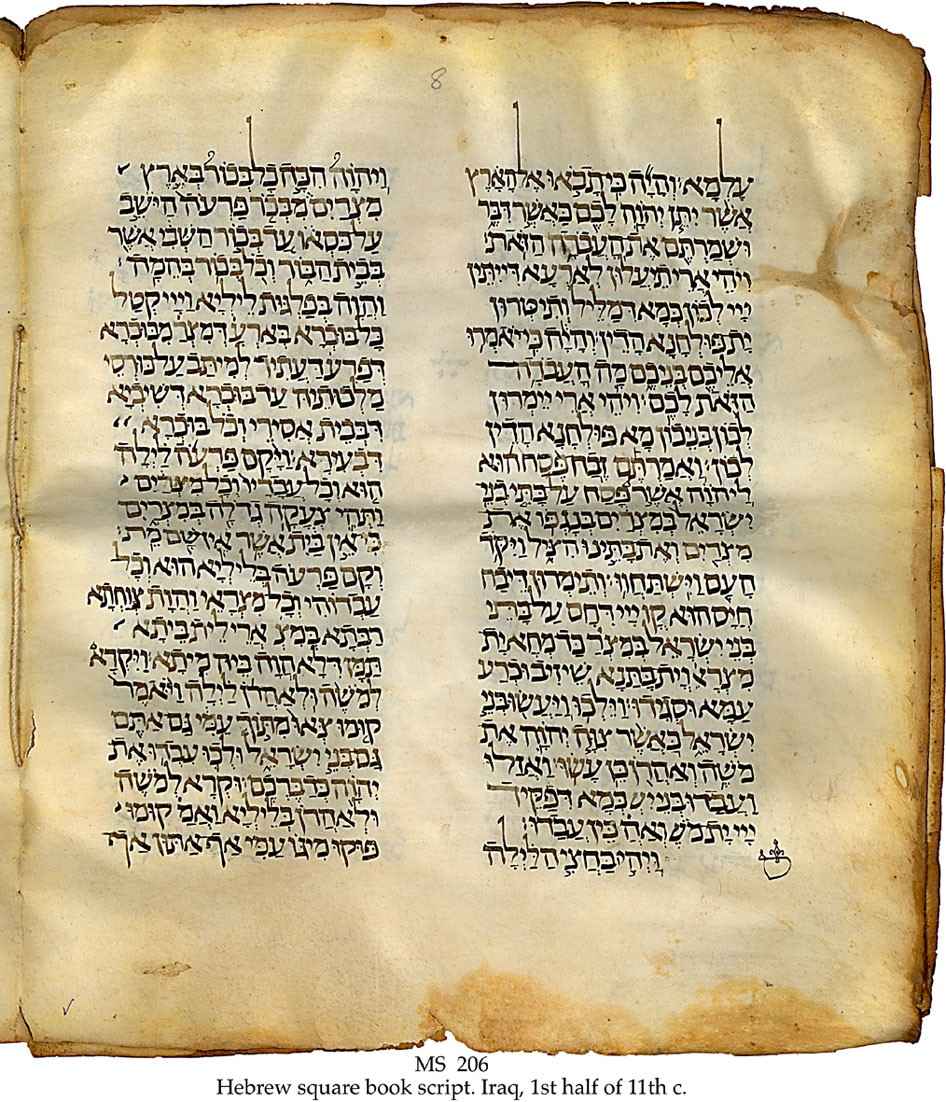

Copies of the Luther Bible include the deuterocanonical books as an intertestamental section between the Old Testament and New Testament;

they are termed the “Apocrypha” in Christian Churches having their origins in the Reformation (image courtesy “Wikipedia”)

By Spencer D Gear PhD

Why would the issue of the contents of the Apocrypha become important for a Christian? Should Christians be reading the Apocrypha as a normal part of Bible reading?

I was alerted to this when I was interacting with an Eastern Orthodox Church (EOC) person or priest on a Christian Forum. He stated:

Saint George’s Cathedral, Istanbul, Turkey (courtesy Wikipedia)

I am personally not prepared to say that nobody outside the EOC, who has heard the Gospel and believed and lived as a Christian, was never saved. Note that the EOC also believes that growth toward God continues after death. I will not say that John Wesley or Mother Theresa will be cast into a lake of fire because they were not under a particular bishop. I will say, though, that I believe that the EOC has the fullness of Christian truth and worship, and that it is where all Christians should be. I also believe that there is need for great humility on all sides, including and maybe especially on ours, as we strive to actually understand what others are saying, and recognize what we have in common rather than focus on what keeps us apart.[1]

In this response, he proceeded to advocate prayer for the dead, praying to the dead, prayer to angels, icons as a meeting point between the living and the dead, the grace of God being active in the relics of the saints, salvation only in the EOC or not.

In an earlier response he stated:

You’ve once again hit on the key difference between us. And it was the key difference for me also, when I first encountered Orthodoxy.

It isn’t what you’re saying, but rather what you are not saying. If I can fill in as best I can, based on our past interactions…

“You provided too many examples…regarding icons…etc…that are not compatible with [my interpretation of Scripture, which is informed from Evangelical Protestant traditions about Scripture, its interpretation and applications, and presuppositions about what the Church is and where it is found, and based on a hermeneutical method of Critical Realism, which largely dates to the 20th Century and is mostly the product of Evangelical Protestant theologians].”

Without mincing words, your hermeneutic (and the philosophy behind it) is a TRADITION. So I have to ask, on what basis is your tradition–or that of McGrath or Wright or other “critical realists”–to be preferred over the much older and much broader orthodox/catholic tradition?

The fact that the answers I gave above, don’t measure up to your understanding of Scripture, could mean that I (and a huge portion of Christians going back to the early Church Fathers on most of those topics) are all wrong. Or, it could mean that your tradition of protestant hermeneutics and critical realism fails to measure up to the tradition of the Church.

Just something for consideration. But really, I’d like to hear your answer on why your tradition of interpreting Scripture, is better than Orthodoxy’s. Where is Critical Realism found in Scripture?[2]

My rejoinder was:

I object strongly to what you did here. I stated:

You provided too many examples in your response regarding icons, communicating with the dead, angels, etc. that are not compatible with Scripture. I would not be pursuing any EOC action.

So what did you do? You distorted and contorted this with your interpretation of what I DID NOT state:

You provided too many examples…regarding icons…etc…that are not compatible with [my interpretation of Scripture, which is informed from Evangelical Protestant traditions about Scripture, its interpretation and applications, and presuppositions about what the Church is and where it is found, and based on a hermeneutical method of Critical Realism, which largely dates to the 20th Century and is mostly the product of Evangelical Protestant theologians.

That is your imposition on what I stated. It is eisegesis of my writings.

Your foray into Critical Realism is a red herring logical fallacy. It doesn’t relate to the topic of the thread. If you have difficulty with a critical realist epistemology, please start a separate thread to address your concerns.

My authority for determining the boundaries of doctrine is Scripture. I do not find these doctrines in Scripture that you affirmed that the EOC teaches:

- praying to the dead;

- prayer to angels;

- icons as a “meeting point” between the temporal and the eternal;

- prayer for the dead;

- The grace of God being active in the relics of the saints;

- salvation is to be found in the EOC;

- The presence of God himself is made real to us in the sacraments.

- growth toward God continues after death;

- I believe that the EOC has the fullness of Christian truth and worship, and that it is where all Christians should be;

- I hold baptism to be necessary but not sufficient [for salvation];

I think that we’ll need to agree that the teachings of our various denominations are incompatible with each other. [3]

Scripture or tradition?

I asked this person:[4] 2 Tim 3:16-17 states: “All Scripture is breathed out by God and profitable for teaching, for reproof, for correction, and for training in righteousness, that the man of God may be competent, equipped for every good work” (ESV).

To which Scripture is Paul referring that is “profitable for teaching, for reproof, for correction, and for training in righteousness”?

He is not telling us which tradition is “profitable for teaching, for reproof, for correction, and for training in righteousness.”

To which Scripture is Paul telling us to go for teaching?

Part of his response was:

In context, he’s referring to the Jewish scriptures with which Timothy had been taught from childhood. I’m not entirely sure just which books Timothy would have considered canonical, but I believe there’s a good chance that the LXX including what came to be called “deuterocanonical books” [the Apocrypha] were part of that corpus. We can’t be 100% sure of the exact bounds of the canon of Scripture at the time this epistle was written. Clearly, Timothy was meant to infer from his own situation, just which Scriptures were being referred to….

As early as Ignatius of Antioch, we see a letter written to the church in Ephesus likely only a few generations after Timothy himself had been a bishop…admonishing his readers to continue in submission to their bishops, elders and deacons.

Clearly, the sufficiency of the Scriptures is not at odds with the authority of the Church’s ordained ministry. It is the task of the entire Church, led by those ordained to that ministry through the laying on of hands, to safeguard the entire tradition received from the Apostles, within which the Scriptures can be properly understood and lived out.[5]

What about the Apocrypha?

What about the Apocrypha?

What were the books of the Jewish Scriptures? Did they include the Apocrypha?[6]

My copy of The Apocrypha (The Oxford Annotated Apocrypha, New York: Oxford University Press, 1973, RSV) states in the Preface and Introduction that:

- “They are not included in the Hebrew Canon of Holy Scripture” (1973:vii); “none of these fifteen books is included in the Hebrew canon of holy Scripture. All of them, however, with the exception of 2 Esdras, are present in copies of the Greek version of the Old Testament known as the Septuagint. The Old Latin translations of the Old Testament, made from the Septuagint, also include them, along with 2 Esdras. As a consequence, many of the early Church Fathers quoted most of these books as authoritative” (1973:x);

- “In the Old Testament Jerome followed the Hebrew canon and by means of prefaces called the reader’s attention to the separate category of the apocryphal books. Subsequent copyists of the Latin Bible, however, were not always careful to transmit Jerome’s prefaces, and during the medieval period the Western Church generally regarded these books as part holy Scriptures” (1973:x);

- “In 1546, the Council of Trent decreed that the Canon of the Old Testament includes them (except the Prayer of Manasseh and 1 and 2 Esdras)” (1973:vii-viii);

- ‘”the Apocrypha” is the designation applied to a collection of fourteen or fifteen books, or portions of books, written during the last two centuries before Christ and the first century of the Christian era’ (1973:ix);

- ‘The terms “protocanonical” and “deuterocanonical” are used to signify respectively those books of Scripture that were received by the entire Church from the beginning as inspired, and those whose inspiration came to be recognized later, after the matter had been disputed by certain Fathers and local churches’ (1973:x);

- ‘The introductory phrase, “Thus says the Lord,” which occurs so frequently in the Old Testament, is conspicuous by its absence from the books of the Apocrypha’ (1973:xii).

- “In the fourth century many Greek Fathers (including Eusebius, Athanasius, Cyril of Jerusalem, Gregory of Nazianzus, Amphilochius, and Epiphanius) came to recognize a distinction between the books in the Hebrew canon and the rest, though the latter were still customarily cited as Scripture” (1973:xiii).

- “In the Latin Church, on the other hand, though opinion has not been unanimous, a generally high regard for the books of the Apocrypha has prevailed” (1973:xiii).

- “At the close of the fourth century, Jerome spoke out decidedly for the Hebrew canon, declaring unreservedly that books which were outside that canon should be classed as apocryphal” (1973:xiii).

- “Disputes over the doctrines of Purgatory and of the efficacy of prayers and Masses for the dead inevitably involved discussion concerning the authority of 2 Maccabees, which contains what was held to be scriptural warrant for them (12:43-45)” (1973:xiv).

The facts are, based on this publication, that the Hebrew canon at the time of the NT writing did not include the Apocrypha.

Some valid questions:

This EOC person left me with some valid and provocative questions:

The list of things from your copy of the apocrypha demonstrates clearly that (a) there were different canons of the OT between the Hebrew-speaking and the Hellenic Jews, (b) that it was the latter that the Early Christians accepted as normative and authoritative.

1. Why do you assume that Timothy, a Greek-speaking Jew from the region of Ephesus, would have not “been taught from his youth” from the Greek translation and canon of the Jewish scriptures?

2. Why grant greater authority to the canonical tradition of the Hebrew-speaking Jews, than to the Greek-speaking?

3. Why grant greater authority to one particular Jewish tradition, than to the Christian tradition itself?

I’d appreciate clear answers to the above, in what little time you can spare. Oh, and one more, a simple yes/no.

*** Do you consider your canon, your methods of interpretation, and your philosophical outlook brought to the texts, to be traditions, or not?[7]

We need to remember that the Apocrypha was from the last 2 centuries before the NT and was not included in the Hebrew canon. It was in the Greek LXX but not the Hebrew canon.

I have not been able to find any NT books that make a direct quotation from any of the 15 books of the Apocrypha although there are often citations from the 39 books of the Hebrew canon of the OT. There may be allusions to some apocryphal books in some NT writers (e.g. Romans 1:20-29 with Wis. 13:5.8; Rom 9:20-23 with Wis.12:12.20; 15:7; 2 Cor 5:1, 4 with Wis. 9:15).

Paul was a Jew and it could be expected that he would communicate with his child in the faith, a Greek-speaking Jew, Timothy, what was in the Hebrew canon. It did not include the Intertestamental books of the Apocrypha.[8]

Eastern Orthodox Church and the Apocrypha

The outlook of the Orthodox Church in America is:

The Old Testament books to which you refer—know[n] in the Orthodox Church as the “longer canon” rather than the “Apocrypha,” as they are known among the Protestants—are accepted by Orthodox Christianity as canonical scripture. These particular books are found only in the Septuagint version of the Old Testament, but not in the Hebrew texts of the rabbis.

These books—Tobit, Judah, more chapters of Esther and Daniel, the Books of Maccabees, the Book of the Wisdom of Solomon, the Book of Sirach, the Prophecy of Baruch, and the Prayer of Manasseh—are considered by the Orthodox to be fully part of the Old testament because they are part of the longer canon that was accepted from the beginning by the early Church.

The same Canon [rule] of Scripture is used by the Roman Catholic Church. In the Jerusalem Bible (RC) these books are intermingled within the Old Testament Books and not placed separately as often in Protestant translations (e.g., 1611 version of KJV).[9]

The Orthodox Christian Information Center provided this assessment:

All Scripture is inspired and, in both St. Paul and St. Timothy’s mind, that meant the LXX. So much is clear. But the LXX included the books we know today as the Apocrypha.

The earliest copies of the Greek Bible we possess, such as the Codex Alexandrinus and Codex Siniaticus [sic] (4-5th centuries) include the Apocrypha. And it is not placed in a separate section in the back of the codex but is rather interspersed by book according to literature type—the historical books with Kings and Chronicles, the wisdom literature with Proverbs and the Song of Solomon, and so forth.

These books were used by the Hellenic Jewish communities and certain Palestinian Jewish groups such as the Essenes. The Apocrypha retained respect in various Jewish communities until around thirty years after Paul’s death when the Pharisees, in the council of Jamnia, and discussed a number of issues, among which was the Jewish canon. Although the influence of this council is disputed, what is clear is that in its aftermath the Apocrypha was decidedly rejected by the Pharisees, who then proceeded to dominate Judaism.[10]

These kinds of comments lead one to accept the Deuterocanonical books (Apocrypha) because:

- These books, being part of the longer canon, were accepted from the beginning of Christianity by the early Church.

- The earliest copies of the Greek Bible (the Septuagint – LXX) include the Apocrypha, not in a separate section at the conclusion of the OT but the books are interspersed throughout the OT according to literature type.

- The Apocryphal books were used by Jewish communities until about the time of Paul.

- See below for an assessment why the Apocrypha should be rejected.

Roman Catholic Church and the Apocrypha

There’s a pretty good overview of the issues surrounding the Apocrypha from a Roman Catholic point of view by A Catholic Response Inc in ‘Apocrypha?’ (1994). The conclusion reached is that

the Catholic Church did not add to the OT. The Catholic OT Canon (also the numbering of the Psalms) came from the ancient Greek Septuagint Bible. Protestants, following the tradition of the Pharisaic Jews, accept the shorter Hebrew Canon, even though the Jews also reject the NT Books. The main problem is that the Bible does not define itself. No where in the Sacred Writings are the divinely inspired Books listed completely. (The Table of Contents is the publishing editor’s words, like the footnotes.) The Bible needs a visible, external authority guided by the Holy Spirit to define both the OT and NT Canons. This authority is the Magisterium of the Catholic Church. As St. Augustine writes, “I would not have believed the Gospel had not the authority of the Church moved me.”

This article also affirms that

the Catholic Church is not alone in accepting the Books which Protestants label as “Apocrypha.” The Coptic, Greek and Russian Orthodox churches also recognize these Books as inspired by God. In 1950 an edition of the OT containing all these Books was officially approved by the Holy Synod of the Greek church. Also the Russian Orthodox church in 1956 published a Russian Bible in Moscow which contained these Books.

I recommend a read of the CatholicCulture.org article, ‘What are the Apocrypha?’ (Hugh Pope 2015).[11] In it, Pope cites St Augustine’s view of the Apocrypha:

Ecclesia Catholica

St. Peter’s Basilica, Vatican City (image courtesy Wikipedia)

Let us omit, then, the fables of those scriptures which are called apocryphal, because their obscure origin was unknown to the fathers from whom the authority of the true Scriptures has been transmitted to us by a most certain and well-ascertained succession. For though there is some truth in these apocryphal writings, yet they contain so many false statements, that they have no canonical authority. We cannot deny that Enoch, the seventh from Adam, left some divine writings, for this is asserted by the Apostle Jude in his canonical epistle. But it is not without reason that these writings have no place in that canon of Scripture which was preserved in the temple of the Hebrew people by the diligence of successive priests; for their antiquity brought them under suspicion, and it was impossible to ascertain whether these were his genuine writings, and they were not brought forward as genuine by the persons who were found to have carefully preserved the canonical books by a successive transmission. So that the writings which are produced under his name, and which contain these fables about the giants, saying that their fathers were not men, are properly judged by prudent men to be not genuine; just as many writings are produced by heretics under the names both of other prophets, and more recently, under the names of the apostles, all of which, after careful examination, have been set apart from canonical authority under the title of Apocrypha (The City of God 15.23.4).[12]

CatholicAnswers asks: ‘Didn’t the Catholic Church add to the Bible?’ (2015). Part of its answer is that

the canon of the entire Bible was essentially settled around the turn of the fourth century. Up until this time, there was disagreement over the canon, and some ten different canonical lists existed, none of which corresponded exactly to what the Bible now contains. Around this time there were no less than five instances when the canon was formally identified: the Synod of Rome (382), the Council of Hippo (393), the Council of Carthage (397), a letter from Pope Innocent I to Exsuperius, Bishop of Toulouse (405), and the Second Council of Carthage (419). In every instance, the canon was identical to what Catholic Bibles contain today. In other words, from the end of the fourth century on, in practice Christians accepted the Catholic Church’s decision in this matter.

By the time of the Reformation, Christians had been using the same 73 books in their Bibles (46 in the Old Testament, 27 in the New Testament)—and thus considering them inspired—for more than 1100 years. This practice changed with Martin Luther, who dropped the deuterocanonical books on nothing more than his own say-so. Protestantism as a whole has followed his lead in this regard.

So, for these Roman Catholic cites give these reasons for accepting the deuterocanonical books:

- The Roman Catholic canon of the OT came from the ancient Septuagint – the OT in Greek that included the Apocrypha.

- The Roman Catholics did not add to the OT books but the Protestants at the time of the Reformation deleted 7 OT books (the Apocrypha) that had been accepted as part of the canon for 1100 years.

- The Bible itself does not define what books should be in or out of the Bible. That is left to the Magisterium of the Roman Catholic Church. So, from the end of the 4th century to the Reformation, the books contained in the Roman Catholic Bible were accepted as the canon.

- Orthodox churches also accept the Apocrypha.

- However, it was conceded what St Augustine stated of the Apocrypha that they contain so many false statements that they cannot have canonical authority.

Hebrew canon of Scripture and the Apocrypha

What did the Hebrews of the Old Testament era consider was the list of books in the Hebrew canon of Scripture?

Why the Apocrypha should be rejected

Ryan Turner has provided an excellent summary on ‘Reasons why the Apocrypha does not belong in the Bible’ (CARM). His major points are:

- Rejection by Jesus and the apostles;

- Rejection by the Jewish community;

- Rejection by many in the Catholic Church;

- False teachings, and

- Not prophetic.

He refers to:

Norman Geisler and Ralph E. MacKenzie, Roman Catholics and Evangelicals: Agreements and Differences. Grand Rapids: Baker, 1995, pp. 157-75.

Norman Geisler, Baker Encyclopedia of Christian Apologetics, Grand Rapids: Baker, 1999, pp. 28-36.

Wayne Jackson has written an excellent assessment: ‘The Apocrypha: Inspired of God?’ (Christian Courier 2015).

Notes

[1] Ignatius#21, 9 June 2014, Christian Forums, General Theology, Salvation (Soteriology), ‘Reasons why you are very unwise to trust your church’s doctrines’ (online). Available at: http://www.christianforums.com/t7825081-4/ (Accessed 24 December 2014).

[2] Ibid., Ignatius21#39.

[3] Ibid., OzSpen#43.

[4] Ibid., OzSpen#57.

[5] Ibid., Ignatius21#58.

[6] These details are in ibid., OzSpen#62.

[7] Ibid., Ignatius21#65.

[8] I mentioned this in ibid., OzSpen#67, #70

[9] Orthodox Church in America, ‘Canon of Scripture’ 2015. Available at: https://oca.org/questions/scripture/canon-of-scripture (Accessed 2 June 2015).

[10] ‘All Scripture is inspired by God’. Available at: http://orthodoxinfo.com/inquirers/otcanon.aspx (Accessed 2 June 2015).

[11] The Catholic University of America Press 2015. Available at: https://www.catholicculture.org/culture/library/view.cfm?recnum=9069 (Accessed 2 June 2015).

[12] The citation from The City of God in CatholicCulture.org is shorter than this version this Augustine publication which I have taken from the Roman Catholic website, New Advent.

Copyright © 2021 Spencer D. Gear. This document last updated at Date: 08 October 2021.

46

46 (walking, talking cross: image courtesy

(walking, talking cross: image courtesy