By Spencer D Gear PhD

What would get Christians up in arms about the best Bible translation?

Try a dialogue with the heading, ‘What is regarded as the best and most accurate version of the Bible?’ on a Christian online forum and the antagonists emerge from the pages of the Bible with Textus Receptus grins or snarls.

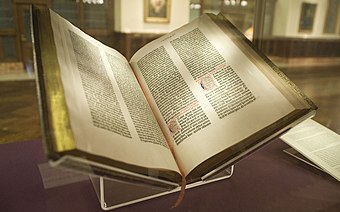

(image courtesy fundamentallyreformed)

This topic led to a particular defender of the King James Version (KJV) of the Bible to come forward, presenting it as the best Bible translation.

1. Difficulties for translators

As the discussion was progressing with the KJV supporter opposing those who supported modern translations such as the NIV and ESV, one of the moderators, gave this excellent example of the difficulties translators face:[1]

When a phrase is translated from one language to another, the translator has no recourse but to do so by expressing a thought. Differences in sentence structure, word meanings, context, and interpretation of the message all play a role. For example, because of the sentence structure differences between languages, to translate a phrase from French or Spanish to English in direct word-for-word form would generally result in a phrase that would not make any sense at all. This is because the order of nouns, verbs, adjectives, etc. are different. Furthermore, some of the French or Spanish words won’t have an English equivalent so what does one do with that? The only choice is to translate the phrase thought-for-thought along with intent-for-intent.

Here’s an example of how changing the order of just one word within a sentence written in English can completely change the meaning of the entire sentence.

Only you can have a sandwich for lunch. When I read this sentence, it is understood that I am the only one that can have a sandwich and nobody else.

You can only have a sandwich for lunch. Moving the word “only” to a different place within the same 8-word sentence and look what happens. Now, it is understood that all I can have is a sandwich for lunch and nothing else. Also, the word “you” could be either singular or plural and possibly addressing a group.

You only can have a sandwich for lunch. Look what happened now. Now, the sentence is confusing. Is this sentence saying that I can have a sandwich and nothing else or is it saying that I am the only one that can have a sandwich and nobody else?

There isn’t a Bible that has been translated into English or any language that is truly accurate. Every one of them is the result of a group of scholars agreeing on the intended meaning. Just like my sample sentence above, just repeating what another has said is really just another form of translation but how the translator understands what is said or written can impact the result.

Whenever we carry on a conversation, the intention of what is said and what is understood can be entirely different. Since we don’t have the original autographed text to work from we are left with ancient writings that had already been translated at least once or more even if within the same language. Therefore, we are stuck trying to piece it all together by combining the reference texts we have.

Even if we did have the original autographed text to work from and we could read and understand the words, we would not agree on the intended meaning of what is written. This is then when we rely on the Holy Spirit to guide us, teach us, and lead us toward understanding God’s intended meaning.

I found this to be a superb example of the challenges many Bible translators face, not only for established ancient and modern English translations but also with translators who work for Wycliffe Bible Translators / SIL and other such organisations.

These latter translators work from the oral language, beginning with translators who know the language, bring it into print (a massive job in understanding grammar and syntax of the oral language). Then they translate Scripture into that language – one book of the Bible at a time. What a job!

Here SIL explains The Typical Process of Bible Translation.

2. A stubborn stickler for the KJV

That splendid response by moderator WIP was on the heels of a KJV supporter who made these kinds of claims:

‘I stick with the good ole KJV that is also free, and is in the “Public Domain”, time honored at 400+ years and going strong!’[2]

‘I stick with the good ole KJV that is also free, and is in the “Public Domain”, time honored at 400+ years and going strong!’[2]

He acknowledged he didn’t stick with the KJV that was 400+ years old: ‘I like the 1769 version, that’s what I use, it revised the old English into middle English’.[3]

2.1 ‘The good ole KJV’

Does being old make it a good translation?

What is the rationality in sticking with ‘the good ole KJV’ that is ‘time honored at 400+ years and still going strong’? The facts are:

He is not reading the KJV that is 400+ years old, but reads the KJV that is 249 years old as of 2018. He misled us with his claim.

He is not reading the KJV that is 400+ years old, but reads the KJV that is 249 years old as of 2018. He misled us with his claim.

![clip_image006[1] clip_image006[1]](https://i0.wp.com/truthchallenge.one/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/clip_image0061_thumb.gif?resize=25%2C25&ssl=1) Because a Bible translation is 400 years old, does that make it better?

Because a Bible translation is 400 years old, does that make it better?

2.2 Imagine using that approach with typewriters.

When was the typewriter invented?

Since the fourteenth century, when the idea of writing machines became technologically feasible, more than one hundred prototype models were created by over 50 inventors around the world. Some of the designs received patents and a few of them were even sold to the public briefly without much success. The first such patent was issued to Henry Mill, a prominent English engineer, in 1714. The first American paten for what might be called a typewriter was granted to William Austin Burt, of Detroit, in 1829.

However, the breakthrough came in 1867 when Christopher Latham Sholes of Milwaukee with the assistance of his friends Carlos Glidden and Samuel W. Soule invented their first typewriter. Sholes’s prototype model, which is still preserved by the Smithsonian Institution, incorporated many if not all the ideas from the early pioneers. The machine “looked something like a cross between a small piano and kitchen table” as one historian observed (Typewriter History 2006).

However, the breakthrough came in 1867 when Christopher Latham Sholes of Milwaukee with the assistance of his friends Carlos Glidden and Samuel W. Soule invented their first typewriter. Sholes’s prototype model, which is still preserved by the Smithsonian Institution, incorporated many if not all the ideas from the early pioneers. The machine “looked something like a cross between a small piano and kitchen table” as one historian observed (Typewriter History 2006).

Prototype of the Sholes and Glidden typewriter, the first commercially successful typewriter, and the first with a QWERTY keyboard (1873) [Wikipedia 2018. s.v. typewriter].

Prototype of the Sholes and Glidden typewriter, the first commercially successful typewriter, and the first with a QWERTY keyboard (1873) [Wikipedia 2018. s.v. typewriter].

Do you know of anyone who demands that the best means to type documents in the twenty-first century is to use the 1867 or 1873 models of a typewriter?

For this article, I use an MS Word 2003 word processor on a Windows 10 operating system and copied the document using WordPress and Open Live Writer to upload to my homepage. I’m encouraged more modern equipment is available in 2020.

It would be idiotic of me to demand that I use the typewriter when so much better technology is available in the 21st century.

But … I know a fellow who has a hard copy of the KJV (1611) that he takes to church every Sunday because ‘this is the best translation of the Bible that does not have verses cut out of it’ (his words to me).

2.3 There are other issues: Byzantine vs Alexandrian text-type

I have addressed some of these in my articles:

I have addressed some of these in my articles:

Does Mark 16:9-20 belong in Scripture?

![clip_image010[1] clip_image010[1]](https://i0.wp.com/truthchallenge.one/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/clip_image0101_thumb-1.gif?resize=48%2C39&ssl=1) The King James Version disagreement: Is the Greek text behind the KJV New Testament superior to that used by modern Bible translations?

The King James Version disagreement: Is the Greek text behind the KJV New Testament superior to that used by modern Bible translations?

![clip_image010[2] clip_image010[2]](https://i0.wp.com/truthchallenge.one/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/clip_image0102_thumb-1.gif?resize=48%2C39&ssl=1) Excuses people make for promoting the King James Version of the Bible

Excuses people make for promoting the King James Version of the Bible

![clip_image010[3] clip_image010[3]](https://i0.wp.com/truthchallenge.one/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/clip_image0103_thumb.gif?resize=48%2C39&ssl=1) The Greek Text, the KJV, and English translations

The Greek Text, the KJV, and English translations

![clip_image010[4] clip_image010[4]](https://i0.wp.com/truthchallenge.one/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/clip_image0104_thumb-1.gif?resize=48%2C39&ssl=1) Corn or grain? KJV or NIV in Matthew 12:1

Corn or grain? KJV or NIV in Matthew 12:1

2.4 Samples of John 3:16 translations in KJV editions

Try these two versions of this verse:

![clip_image006[2] clip_image006[2]](https://i0.wp.com/truthchallenge.one/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/clip_image0062_thumb.gif?resize=25%2C25&ssl=1) KJV (1611): ‘For God so loued þe world, that he gaue his only begotten Sonne: that whosoeuer beleeueth in him, should not perish, but haue euerlasting life’.

KJV (1611): ‘For God so loued þe world, that he gaue his only begotten Sonne: that whosoeuer beleeueth in him, should not perish, but haue euerlasting life’.

Is that how English people speak and spell in the 21st century?

Why would anyone want to read in church the language of 1611 or share the Gospel with people using that kind of translation? It would reinforce the views of some secularists that the Bible is an out-dated book for an obsolete religion.

Generally, it is because there is a small band of KJV-only supporters who use this approach:

![clip_image006[3] clip_image006[3]](https://i0.wp.com/truthchallenge.one/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/clip_image0063_thumb.gif?resize=25%2C25&ssl=1) They try to demonstrate that the Textus Receptus, compiled by a Dutch Roman Catholic priest and humanist, Desiderius Erasmus (1466-1536) is the best translation.

They try to demonstrate that the Textus Receptus, compiled by a Dutch Roman Catholic priest and humanist, Desiderius Erasmus (1466-1536) is the best translation.

![clip_image006[4] clip_image006[4]](https://i0.wp.com/truthchallenge.one/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/clip_image0064_thumb.gif?resize=25%2C25&ssl=1) KJV (1769 rev ed): ‘ For God so loved the world, that he gave his only begotten Son, that whosoever believeth in him should not perish, but have everlasting life’ is the version most KJV enthusiasts use, but it also is a revised version, but based on the Textus Receptus.

KJV (1769 rev ed): ‘ For God so loved the world, that he gave his only begotten Son, that whosoever believeth in him should not perish, but have everlasting life’ is the version most KJV enthusiasts use, but it also is a revised version, but based on the Textus Receptus.

If a person is fixated on reading from the KJV and using the Greek Textus Receptus for the NT translation, wouldn’t this be more appropriate for the current century than 1611 language?

![clip_image006[5] clip_image006[5]](https://i0.wp.com/truthchallenge.one/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/clip_image0065_thumb.gif?resize=25%2C25&ssl=1) King James 2000 Bible: ‘For God so loved the world, that he gave his only begotten Son, that whosoever believes in him should not perish, but have everlasting life’.

King James 2000 Bible: ‘For God so loved the world, that he gave his only begotten Son, that whosoever believes in him should not perish, but have everlasting life’.

![clip_image006[6] clip_image006[6]](https://i0.wp.com/truthchallenge.one/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/clip_image0066_thumb.gif?resize=25%2C25&ssl=1) Or, the NKJV: ‘For God so loved the world that He gave His only begotten Son, that whoever believes in Him should not perish but have everlasting life’.

Or, the NKJV: ‘For God so loved the world that He gave His only begotten Son, that whoever believes in Him should not perish but have everlasting life’.

‘I like to share God’s word as found in Matthew 17:21, 18:11, Acts 8:37, Romans 16:24 [from Textus Receptus and in KJV].

‘I like to share God’s word as found in Matthew 17:21, 18:11, Acts 8:37, Romans 16:24 [from Textus Receptus and in KJV].

Can’t use the NIV, ESV, the verses are not there’.[4]

‘The fact stands today that over 5,000 Majority reading textual family witnesses exist.

‘The fact stands today that over 5,000 Majority reading textual family witnesses exist.

The Alexandrian textual family is roughly at 50 witnesses; this is how the 99/1 ratio is determined’.[5]

‘I have clearly shown you the fact of history, the church outside of Egypt didn’t use or transmit the Alexandrian Minority Text, This Is A Fact.

‘I have clearly shown you the fact of history, the church outside of Egypt didn’t use or transmit the Alexandrian Minority Text, This Is A Fact.

Westcott & Hort in 1881 revived the Alexandrian Text and published it to the world.

St. Jerome (Jerusalem) 347-420AD maintained knowledge of the Alexandrian schools, and he didn’t use their textual readings in his (Latin Vulgate)?’[6]

Why is the Alexandrian text-type out of the city of Alexandria – a port city in northern Egypt – the supposed ‘minority text-type’? In contrast, why is the Byzantine text-type the majority text-type?

3. It is quite simple to explain according to KJV promoters.

This is one example readily available to me.

‘The argument is the Majority Greek Text 99% or the Alexandrian Minority Greek Text 1% of MSS.

‘The argument is the Majority Greek Text 99% or the Alexandrian Minority Greek Text 1% of MSS.

The 57 KJV Translators were fully aware of the 1% minority text, and they didn’t use it because of it never being used or received by the early church.

The Alexandrian 1% minority text was basically localised to Egypt, the Church never used or received this text, A historical fact’.[7]

3.1 What are some other reasons?

Why is the Alexandrian text-type of, say, Codex Sinaiticus or Codex Vaticanus so small a representative of Greek MSS when it was closer to the original documents than the Byzantine text-type?

In light of the above objections, I find it necessary to examine some background to the Byzantine text-type, the Textus Receptus behind the KJV, and the Greek text gathered by Erasmus (died 1536).

Is the KJV a superior Bible version and have the modern versions been corrupted by Westcott & Hort’s ideology of Alexandrian text-type in gathering NT manuscripts?

A part of page 336 of Erasmus’s Greek Testament, the first “Textus Receptus.”

Shown is a portion of John 18.[8]

In my article, The King James Version disagreement: Is the Greek text behind the KJV New Testament superior to that used by modern Bible translations?[1], I have listed 13 sound reasons for regarding the Textus Receptus behind the NT of the King James Version as not being superior to that used by the modern Greek critical text.

In my article, The King James Version disagreement: Is the Greek text behind the KJV New Testament superior to that used by modern Bible translations?[1], I have listed 13 sound reasons for regarding the Textus Receptus behind the NT of the King James Version as not being superior to that used by the modern Greek critical text.

4. Conclusion

I recommend you visit that article for an assessment of the Byzantine vs Alexandrian text-type. Please note that most modern translations of the Bible use the critical text of the Alexandrian text-type e.g. RSV, NRSV, ESV, NIV, NIRV, NLT, NET, ERV, REB, HCSB, JB, NAB, and NASB. Those using the Byzantine TR include the KJV 1611, KJV 1769 (rev), NKJV, Mounce Reverse-Interlinear, and others translated around the time of the KJV – John Wycliffe Bible, Tyndale, Coverdale, Matthew’s, The Great Bible, Geneva Bible, and Bishops’ Bible, Later versions using the TR include Webster’s Bible, Julia E Smith’s Bible, J P Green’s Literal Translation, and the Revised Young’s Literal Translation.[9]

The Erasmus Greek text that became the Textus Receptus and had so much influence on the text used for the translation of the KJV New Testament, is based on a ‘debased form of the Greek Testament’ (Metzger’s words).[10]

Better Greek manuscripts are available in the twenty-first century and most of the new translations are based on these texts. The Greek texts gathered by Erasmus that became the Textus Receptus are not the most reliable Greek texts available for NT translation.

The manuscripts found since the time of Erasmus and the eclectic Greek text of Nestle-Aland 26, which is used in the United Bible Societies Greek NT (edition 27 is now available), provide a more reliable Greek text from which to translate. The latter Greek text is used in such English Bible translations as the RSV, NRSV, ESV, NET, NIV, NASB and NLT.

However, there is no point in trying to convince a dogmatic KJV-only supporters of these details.[11] They are inflexible in considering another alternative. I wish these people well with a greeting such as, ‘We’ll need to agree to disagree. God bless and encourage you’.

To my knowledge, no major Christian doctrine is affected if one of these textual lines of transmission is preferred over the other.

5. Works consulted

Metzger, B M 1964/1992. The text of the New Testament: Its transmission, corruption, and restoration (third, enlarged, edition). Oxford: Oxford University Press Inc.

6. Notes

[1] Christian Forums.net 2018. What is regarded the best and most accurate version of the Bible? (online), WIP#99, 24 June. Available at: https://christianforums.net/Fellowship/index.php?threads/what-is-regarded-the-best-and-most-accurate-version-of-the-bible.76719/page-5#post-1469744 (Accessed 25 June 2018).

[2] Ibid., Truth7t7#64, 23 June 2018.

[3] Ibid., Truth7t7#70.

[4] Ibid., Truth7t7#74.

[5] Ibid., Truth7t7#48,

[6] Ibid., Truth7t7#52.

[7] Ibid., Truth7t7#32.

[8] Available at: http://www.skypoint.com/members/waltzmn/TR.html (Accessed 18 January 2019).

[9] With assistance from Textus Receptus Bibles 2019. Available at: http://textusreceptusbibles.com/ (Accessed 18 January 2019).

[10] Metzger (1964/1992:103).

[11] The last 3 paragraphs of the conclusion are taken from the conclusion of my article, The Greek Text, the KJV, and English translations.

Copyright © 2020 Spencer D. Gear. This document last updated at Date: 21 March 2020.

![]() Old Testament documents confirmed as reliable again[1]

Old Testament documents confirmed as reliable again[1]![]() The Bible as reliable history.

The Bible as reliable history.![]() Does the New Testament contain history or myth?

Does the New Testament contain history or myth?![]() To speak about ‘dim-witted theists’ reveals: (a) his use of an ad hominem (abusive) fallacy. These people need to be called out for what they do to a discussion.

To speak about ‘dim-witted theists’ reveals: (a) his use of an ad hominem (abusive) fallacy. These people need to be called out for what they do to a discussion.![]() and (b) demonstrates his presuppositions of shaming Christian religion, but without providing evidence to support his claims. To call a theist a ‘dim-wit’ without evidence is to demonstrate shallowness of the claim.

and (b) demonstrates his presuppositions of shaming Christian religion, but without providing evidence to support his claims. To call a theist a ‘dim-wit’ without evidence is to demonstrate shallowness of the claim.![]()